Dave Lowe describes his career with a joke that lands because it’s true: he’ll do anything for a check—as long as it’s creative. It’s not cynicism. It’s range. It’s the earned flexibility of someone who can draw, paint, build, carve, fabricate, design, and write, then shift gears without losing the thread of his own voice.

He’s been in Burbank since he moved to Los Angeles in 1987, part of the city’s quietly enormous creative workforce—the kind that keeps productions moving, public art looking alive, and community projects feeling handcrafted instead of generic. And while his résumé stretches across entertainment, fabrication, and civic commissions, the engine under all of it is simple: Dave loves making things, and he loves the moment when something in your head becomes something in the world.

Before L.A., there was New York—where he was born and raised—and then Providence, Rhode Island, where he attended the Rhode Island School of Design. At RISD, he aimed himself at a very specific dream: children’s book illustration, or illustration in any form. He gravitated toward the cartoony end of the spectrum, raised on Warner Bros. Looney Tunes, Saturday morning cartoons, and comic books. In his mind, the future looked like Disney, Marvel, or the classic daily newspaper strip route—Charles Schulz, Gary Larson, that lineage. School, by his own account, wasn’t his arena. Art was. Drawing was the thing that made sense.

Dave’s parents were supportive, and a key influence arrived through family: his mother, seeing how deeply he loved comics and cartoons, pointed him toward a different kind of image-maker—N.C. Wyeth. That one nudge opened a door to the Wyeth family’s legacy and to the broader world of American illustration: Andrew Wyeth, Norman Rockwell, Howard Pyle. Suddenly, the target wasn’t just “cartoons.” It was craft. Draftsmanship. Story. The ability to make a single image hold a whole narrative.

That discovery came with another realization: if he wanted to do this seriously, he needed formal training. His high school didn’t have much of an art department, so he sought it out—summer classes, figure drawing, the fundamentals you don’t really absorb from books. And maybe most importantly, he found community. Before the internet, it was easy to feel isolated in a town where you might have one friend who drew. Art school replaced isolation with peers: a room full of people who carried sketchbooks like oxygen. It wasn’t a hobby there. It was a craft you studied.

Then life bent the map. While Dave was in college, his father’s producing and directing work took the family to Los Angeles often, and eventually they moved permanently. Dave came out after graduation expecting a five-year adventure. Instead, L.A. became home, and Burbank became the long-term base for a career that kept expanding into new skills.

When he arrived, the children’s book market in Los Angeles felt small and hard to break into. He found some small publishers—workbooks, little projects—enough to keep the identity alive but not enough to keep the lights on. Illustration also has a harsh math problem: even a simple black-and-white book can take months, and you don’t get paid until long after the labor. So Dave did what so many creatives do in the early years: he cobbled together survival. He worked at Aaron Brothers Art Mart and learned framing. He took whatever jobs came up. He tried the classic doors—dropping portfolios at Disney, sending material to syndicates, absorbing rejection slips like weather.

The pivot happened because of proximity and timing. Dave’s father knew producers staffing up for a Nickelodeon kids’ show, Wild and Crazy Kids, and suggested a production assistant job—at least a summer paycheck. Dave said yes. And that “yes” turned into a turning point.

Wild and Crazy Kids was low-budget, chaotic, and perfect. There was no robust art department, and the show needed constant making—crazy games, giant game boards, oversized props, painted numbers, whipped-cream water balloons. Dave thrived in the scramble. Producers started deferring to him: “Get Dave to do it—Dave can paint it, Dave can build it.” Within the mess was an invitation: not just to execute, but to design.

From there, the work spread through networks. In the early ’90s, channels like the Sci‑Fi Channel and HGTV were still new, with tiny budgets and big needs. Producers moved on to new shows and brought Dave with them. One of them hired him for a Sci‑Fi Channel program called Sci‑Fi Buzz—an entertainment news show filtered through science fiction. They needed a set, and Dave had never built a full four-wall set before. He dove in anyway.

He describes that era with refreshing honesty: either he was too inexperienced to realize how much he didn’t know, or he loved the process enough not to be afraid. Both can be true. He learned by doing, brought in friends with complementary skills—a good carpenter, other makers—and slowly the “career” began to look like a system. Eight years later, he was being hired as a prop master, a set designer, a builder, an illustrator when needed. The phone rang. Dave jumped. Sometimes he was in over his head. Sometimes the job was glorious. Either way, he came out with new skills.

Eventually, he reached the moment every working creative recognizes: the shift from “take everything” to “choose your direction.” At first, saying yes was survival. Later, saying yes became strategy—because each new skill expanded what he could offer. And when he wanted to steer toward work that gave him more authorship, he found himself repeatedly returning to a theme: projects that felt public, community-based, and personally expressive.

That’s where Burbank enters the story as more than a zip code. Dave walked out one day and saw artists painting utility boxes along Riverside Drive—a sudden burst of public creativity he hadn’t expected to encounter on a coffee run. He asked questions, found the application, submitted designs, and eventually painted a box himself. It was the kind of project that hit a sweet spot: small enough to handle, public enough to matter, and free enough that he could be fully himself.

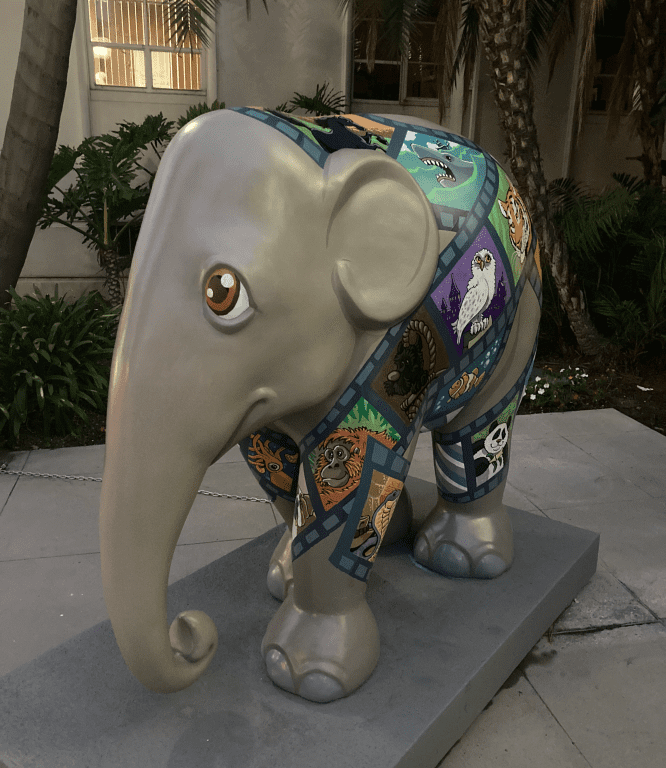

Next came the Elephant Parade project. Dave submitted a design, was accepted, and spent two weeks painting an elephant in front of City Hall—an experience that combined civic visibility with the simple pleasure of craft. Today that elephant lives at the Betsy Lueke Creative Arts Center, a physical reminder that community art can be both playful and permanent.

For Dave, those projects formed what he jokingly calls a Burbank “triple crown”: the utility box, the elephant, and then—finally—the Tournament of Roses float design.

The Rose Parade had been in his imagination for years. In the mid-’90s, he spent New Year’s with friends in Pasadena, walking to the parade route for coffee, breakfast, and the tail end of the spectacle. Someone told him, “Dave, you’d be great at designing floats—it’s your style, your humor.” He filed the idea away.

Years later, curiosity turned into action. He found the Burbank Tournament of Roses application and submitted. His first attempt didn’t make it, and he suspects he overthought it—especially because the submission window used to require designs based on a hint, not the full theme. Another year he missed the deadline by two days. The experience was familiar: take your shot, accept the odds, keep moving.

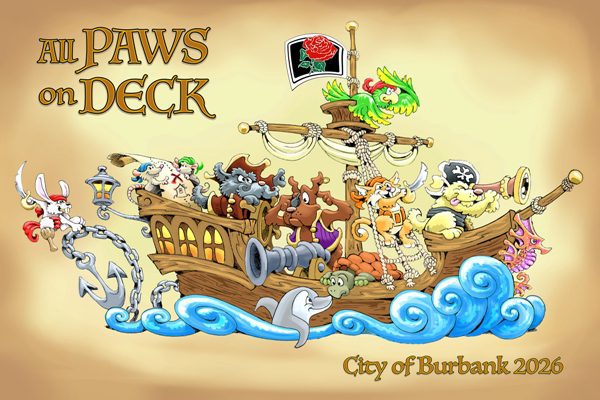

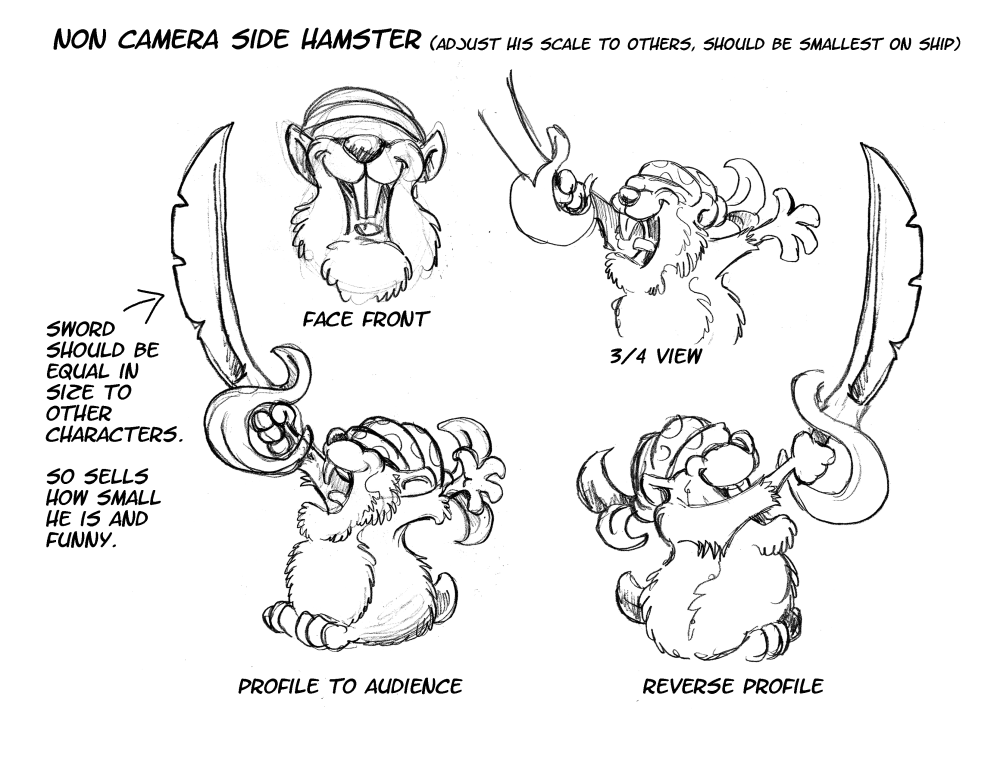

Then came the 2026 season hint—people coming together for a common cause, eventually revealed as “teamwork.” This time, Dave made a decision that changed everything: don’t design for approval. Design for delight. What would he want to see as a float? He started doodling. He loves pirates, so a pirate ship emerged. Then his instincts moved toward animals—because people love animals and he loves animals. Why are they together? Because they’re pirates. Why pirates? Because they’re strays looking for a home—their “treasure” is adoption. It clicked into a playful, heartfelt concept built on a simple emotional engine.

He made three or four versions, chose the most finished, scanned it, printed it, and dropped it into a submission box at a committee member’s house—where the pile of entries was already huge. He didn’t expect much beyond the satisfaction of having made something fun.

Three weeks later, he got the call: he’d been chosen.

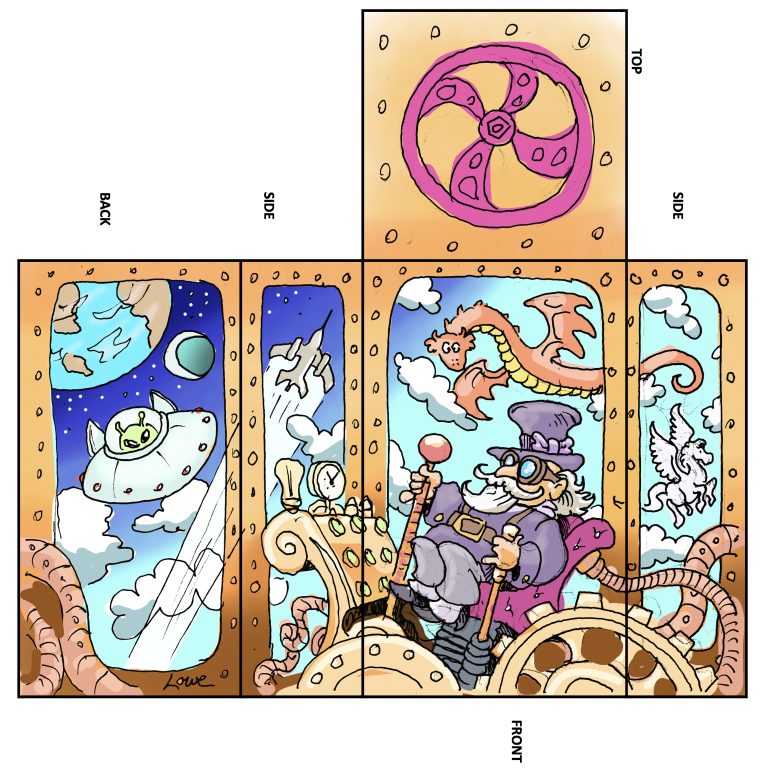

Winning was only the beginning. Dave assumed the process might be passive—submit a design, watch the organization run with it. Instead, he was invited into a collaborative production pipeline: design meetings with the full committee, lead floral decorator, construction leads, department heads. The drawing went up on the wall. Notes flew. Ideas pinged around the room. Revisions followed. Then more meetings. Then sign-off.

He loved the process because it was “committee” in the best way: not bureaucratic, but collective. Everyone cared. Everyone had ideas. Nobody shut down wild suggestions. The focus was always: how do we make it better?

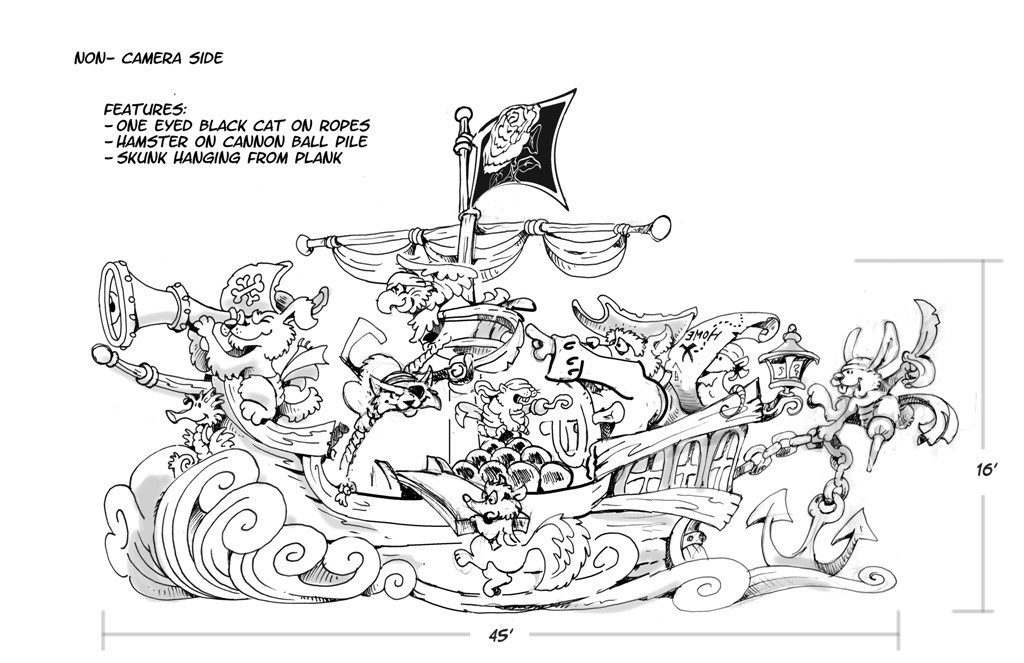

That collaboration also taught him float-specific truths that even experienced set builders can overlook. A float isn’t just designed for a camera side; it must read from both sides for spectators. Most viewers are at ground level, looking up, meaning elements that feel visible in an artist’s mind might disappear in real-world sightlines. Those conversations pushed Dave to add characters lower on the far side—fun hidden details many people never even knew were there. And because his career has been a buffet of making—foam carving, prop builds, set construction—he could understand every craft step, even as he wisely deferred to the team members with decades of float experience.

At one point, he tossed out a playful idea—a kraken. The team loved it enough to add tentacle arms curling off the other side of the ship. That’s the kind of detail that reveals the float’s spirit: not only spectacle, but joy.

Looking back, Dave recognizes a satisfying irony. On the morning of judging, he stepped back and realized: he knew how to do all of this. Over the years, he’d learned welding, carving, fabrication, painting, scenic tricks like rust and patina—skills built from necessity on low budgets and impossible deadlines. The float simply gathered those threads into one giant, rolling object.

And yet, what seems to matter most to him isn’t scale. It’s authorship. It’s the difference between building someone else’s vision and building something that feels like yours—even when it takes a village to execute. Dave has had both kinds of work, and he values the relationships either way. But you can hear the extra spark when he talks about projects where nobody is standing over his shoulder, where the community becomes the audience, and where the object carries his humor and his hand.

At home, he still makes “artifacts” and “oddities”—found-object curiosities meant for a shelf, the kind of thing you might discover in a cabinet of wonders. He loves transforming garbage into believable detail, an approach rooted in the great special-effects tradition—Ray Harryhausen, Industrial Light & Magic, the old-school makers who turned junk into magic. Sometimes he worries that using found objects is “cheating,” until he sees how much people love the transformation. Watching someone lean in and ask, “How did you build that?” never gets old.

In the end, Dave Lowe’s story isn’t a straight line from RISD to a single title. It’s a life made of skills collected like tools in a belt: illustration, scenic, props, sets, public art, and big communal builds. The throughline is curiosity plus courage—the willingness to dive in, learn fast, and keep going. That’s what keeps him in Burbank, still making: not because the path was easy, but because the work keeps turning into something real.

Originally published in www.theburbankblabla.com. Living Arts Magazine