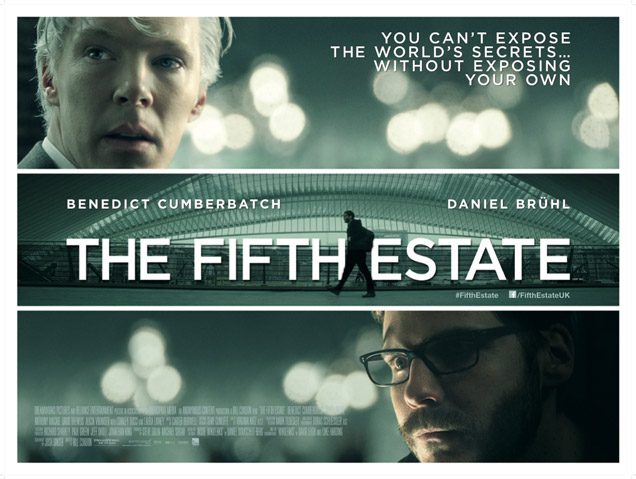

Modern media and our ever-expanding age of technology have changed the face of journalism. Traditional media has often been coined the “fourth estate” or a fourth branch of government to ensure proper checks and balances. Now, our media landscape has shifted and a new branch has been introduced. The “fifth estate” now represents citizen journalism, or participatory journalism. This new trend of journalism was introduced and highlighted in the film “The Fifth Estate.” The film was inspired by the events surrounding WikiLeaks, an organization that was created by Julian Assange, meant to promote transparency by publishing classified documents revealing government, business and war secrets.

The film had a weak opening and has been considered a flop by many critics, as they debate the execution, purpose and validity of the film. However, “The Fifth Estate” raises an important ethical issue. Which is more important? Seeking truth in society or protecting the lives of innocent people.

In the film, Assange (Benedict Cumberbatch) is portrayed as a cold and moderately aloof tech genius who is determined to encourage active citizen participation and freedom of information by exposing classified secrets that could destroy oppressive regimes. He is seen as a manipulator and borderline lunatic as he pursues his quest.

“The Fifth Estate” was denounced by the real Assange as “propaganda” and WikiLeaks subsequently posted a statement on their website stating their issues with the film and it’s legitimacy.

However, even taking the film with a grain of salt gives us insight into the current struggle our society is facing with the emergence of citizen journalism. In the film, Assange’s idea is that government does not actually exist to protect the individual, which is seen through their efforts to cover up the incriminating information; In contrast, it is the citizen journalists and whistle blowers who seek to protect the individual by providing them with important information about the inner workings of government and business. It is the citizen journalists who are actually looking out for us, according to Assange.

While details surrounding the events leading up to WikiLeaks, like Daniel Berg’s actual role in WikiLeaks and the claim that Assange was in a cult may be false, viewers are welcomed into the fight for government transparency and accountability.

“The Fifth Estate” depicts the fight for freedom of communication and as well as the issue of national security and civilian safety.

In “The Fifth Estate,” Assange was adamant that regardless of risk, freedom of information is the most important thing citizen journalists can achieve. He was firm in his belief that any documents WikiLeaks received must not be edited, as that undermines the effort to provide complete and honest information.

The real Assange denounces his portrayal in the film as misleading and false.

“‘The Fifth Estate’ presents Julian Assange as a transparency zealot who believes everything should be made public, but this is wrong,” according to the WikiLeaks website.

In the statement, it is noted that while Assange is an advocate for government transparency, he strongly believes in the individual’s right to privacy, and thinks that “transparency should be in proportion to power.”

This idea is something that WikiLeaks believes was misleading about the film, and to its defense, it is a question that remains with the viewer at the end of the film. Assange’s belief in transparency was portrayed as a very broad idea in the film, a blanket idea with no boundaries or exceptions. In order to truly understand Assange’s ultimate goals, it must be understood that he believes in government transparency and personal privacy.

The film was also purposeful in nuancing the differences and perhaps, dangers of citizen journalism and traditional journalism. In the film, The Guardian worked with Assange to help break the story of the leaked Afghanistan War Logs, but they were determined to do so with decency by redacting any names of private individuals. This was another issue that the real Assange denounced as false. Assange claimed that The Guardian’s redactions distorted the news and that there is no proof WikiLeaks put anyone in danger.

Perhaps one of the main issues of citizen journalism and a question that was raised in

“The Fifth Estate” is this: if citizen journalists abide by no guidelines, how can we trust they will be ethical and decent in their work? How can we trust their sources? We can’t be sure they verify the information they receive. “The Fifth Estate” depicts the serious issues surrounding citizen journalists who follow no rules. Assange was determined to do what he thought was right and wasn’t going to give in to anyone. Regardless of whether or not the real Assange believes this portrayal to be accurate, it is a problem our society now faces with citizen journalists in general.

While many critics will pick out all of the problems with the film, and there are many, it seems to be best to look at the main idea. The main point made in “The Fifth Estate” is to question journalism; both traditional and citizen. It is a question of checking on our government to ensure our leaders are being ethical and to stop tyranny around the world. But ultimately, it is a question in execution.

Many Americans today applaud Assange’s efforts to reveal corruption and war crimes by providing information on a global level. Citizens have a right to be informed, and when our government fails to do so, someone must pick up the slack. Assange’s intent is to promote freedom and inspire honesty and truth across the world while denouncing tyranny and corruption. Their message is one that is important for global citizens to adopt. However, ethical implications of such openness must be considered. In matters of national security, whistle blowers and investigative/citizen journalists must heed caution because the material they are revealing is sensitive, classified and in many cases, could completely ruin the reputation of governments around the world.

“The Fifth Estate” is currently playing at the AMC 16 in Burbank.